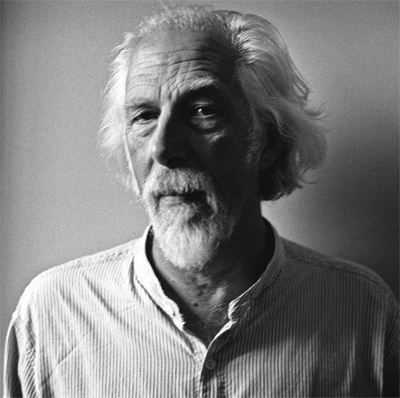

‘I was born in London in 1950 and grew up in a basement in Holland Park Avenue. My grandmother and great-grandmother lived above us. It was real old-fashioned Kensington but surrounded by, as I recall, bombsites. I remember London in that period as very grey. It lacked colour. I remember the buses were red and the sky blue etcetera, but otherwise it was a very colourless place. I was then dispatched to boarding school in Buckinghamshire at age 7½. Far too young to be sent away I thought, and I remember thinking later that, for eleven years I never spent the months of February, May or October at home. My parents moved to Hampshire around the same time and to me it was very rural. They bought a beautiful old timber-framed cottage near Selborne and I remember Tom Chiverton, the gardener, taking his bath in a tin tub outside his back door. You wouldn’t recognise it now for Volvo estates and carriage lamps. So I had a very idyllic childhood really, I was very lucky. I then went on to Stowe where I was in the same class as Richard Branson. He did rather better than me in retrospect. I didn’t get on very well with Stowe and although one was expected to go to University, ideally Oxford or Cambridge, I opted for a few months cruising around Morocco with a friend. It was 1968 after all and having a career wasn’t exactly fashionable at that time.

However, I did eventually do an Arts foundation course at Farnham School of Art followed by Graphic Design at Wimbledon. Graphic Design had become rather groovy in the sixties. No longer was it looked down on as ‘commercial art’. And I had always been interested in photography. I remember when I was young discovering my father’s photograph albums and being fascinated by the details in the pictures. At college we had a succession of brilliant visiting lecturers, one of whom was an American photojournalist called John Benton-Harris who introduced me to the work of Tony Ray Jones, the celebrated English documentary photographer and the Americans Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank who had taken black and white photography onto the streets. Like everyone else at that time, I wanted to be Cartier Bresson.

Although Benton-Harris had advised me never to take commissions from newspapers, or from anyone else for that matter – he thought anything commercial was “full of sh*t” – I still had to get a job. So I signed up with a recruitment agency who got me a job as an assistant to a fashion photographer. It was a bit like working in a sweatshop but I did it for a year and got paid twelve pounds a week. I was able to top up with overtime work, taking photographs of wanna-be models, ninety percent of whom had no hope whatsoever of getting any work. It was not my thing at all. I had no interest in fashion photography, nor any interest in clothes, but I had the use of his studio and the use of his darkroom, which meant I could just get on with my own stuff.

After that I went to work for Michael Boys which was working on a whole different level. I learned about sheer professionalism and about working in colour. I went from twelve quid a week to six pounds a day. At weekends Michael would let me use the firm’s car and sometimes he’d say, “George let’s a take a couple of days off and go sailing” and off we’d go. He really looked after people. He fired me in the end because he thought I was nicking some of his clients. However, we remained friends and I still worked for him occasionally after that.

So I had accumulated quite a portfolio and one of the models that was looking for work had some of my photographs in her book, so I got commissioned to do a fashion shoot. Suddenly I was on £100 a day instead of £6. So I thought, great I’ll give this a go and I’ll allow myself time off every year to try and do some of the pictures I think I should be doing. I had a tiny studio so decided I would do a lot of location photography and it was fun.

I remember one trip in the mid-seventies with a friend called Emma Parsons and her boyfriend, the journalist Roger Cooper, who was later to spend 6 years in solitary confinement in Evin prison in Tehran, (when asked on his release how he survived with the ordeal, ‘Mrs Thatcher’s Spy’ put it down to his time at an English public school!). He decided we should drive his VW camper from Gloucester Road to Kuwait. He was working for the Sunday Times and the idea was that he would interview all sorts of important people and we would submit these stories to the newspaper. So off we went. Fortunately, Emma’s father was a diplomat so we had letters of introduction to various embassies and I recall one occasion when we arrived in Damascus and hadn’t yet got visas for Iraq. So we presented our letter to the ambassador and had dinner with him. As the next day was Sunday we invited him to have Sunday lunch with us in our camper van. So we parked up outside the embassy compound, and he took one look at it and suggested we might be more comfortable in the garden. So there was this wonderful scene where these white-coated servants came out to collect this unlikely meal we had cooked for the ambassador.

During the same trip we ended up in Djibouti where we came across this extraordinary refugee camp outside a barbed wire fence which the Djiboutians had erected after receiving independence from the French. There were these poor guys who had fled from Addis Ababa and there were qualified doctors, aeronautical engineers, highly intelligent people living in cardboard boxes. It was like a sort of forgotten refugee camp.

It was after that trip that I started to work for the Observer. The picture editor was Colin Jacobson and he sent me all over the place. Jane Grigson was the food writer so when Jane was doing a guide to European food I would go off to Spain, Italy, Ireland, France or wherever. Eric Newby was their travel writer. And Christopher Lloyd was their gardening writer and photographing gardens was one of my big interests. I decided that English gardens should be photographed in English weather so I went for shots of the potting shed and that sort of thing. I was very lucky. I came in at the end of the golden era for the colour supplements – the end of the eighties.

I have photographed so many people over the years. Harold Acton in Florence, Russell Harty in East Berlin. The Observer did a regular feature called Room of my Own and I used to get those to do. I was asked to photograph Ted Hughes, who at first said no because he ‘didn’t believe in the cult of the personality’. It was my job to change his mind and he turned out to be absolutely delightful. Tom Sharpe I photographed in Bridport for an article by Anna Pavord called Disaster in the Deep Bed. I went to his house and he had a lovely garden but he parked his ride-on mower in a dog kennel and it looked like it had just crashed into it. A typical Tom Sharpe scenario. He gave me lunch afterwards which consisted of great huge bulbs of raw garlic.

My career has taken me all over the world from the Yemen to Irian Jaya. I moved to Dorset in the mid-eighties and bought what was advertised as ‘a remote farmhouse in need of modernisation’. I bought it at auction for the same amount I had sold my property in London for, so it was a straight swop. That was when I started doing the photographs that were used in Vanishing Dorset. I started photographing my neighbours and began to notice how things were literally vanishing around me. I used to drive past old farmer Wallbridge’s house and could see this amazing interior lit by one naked light bulb. Then when the place was going to be auctioned his sons let me in to photograph it. I hadn’t planned a book, I was just photographing for posterity, but the more I did it the more I could see disappearing. And the boom in DIY stores meant that these individual windows, doors even wallpaper would be gone forever, replaced by plastic. I’m a great fan of rusty corrugated iron.

I have never thrown away a photograph in my life. I probably have between five and ten thousand little Kodachrome boxes, each containing thirty-six slides. I will go through them eventually and maybe I’ll select fifty that have slipped through the net, but the rest, who knows what will happen to them?’