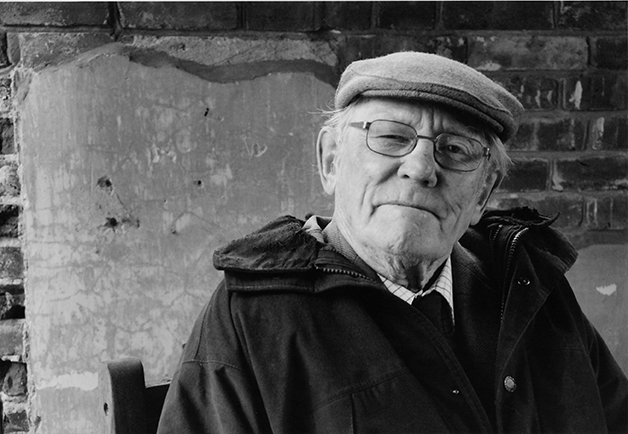

‘I was born in London, but that was not my fault, in 1924. My parents moved into Symondsbury Manor when I was a few months old. My two younger sisters followed, also born in London. I remember my Mother returning with the babies and wondering why babies should always come from London.

The first world war was six years past and life in Manor Houses in those days was different. The House was fully staffed. Butler, head housemaid, two under housemaids. Two in the kitchen. That sort of thing. My father was the MP. I remember election times. A proper bustle. Always meals on hand. The kitchen full of good things to eat. No television elections in those days. All done with public meetings. I remember my father being asked by Strange who was head gardener, (everyone was called by their surname in those days), what question he should ask the Liberal Candidate when he came to Symondsbury. My father told him to ask if he could find his way to Halstock in the dark. Being local was a plus point. Mr Chapel, the Liberal candidate, was a nonconformist minister and came from Wales. As it happened, Mr Chapel had booked a meeting in Halstock the night before and had got lost and never turned up. Hoots of delight and a political point scored. I remember the consternation at one election when Mr Chapel said to my father that he would lose the election, to which he replied that if Mr Chapel thought that, he was a bigger BF than he, my father, realised. “Conservative Candidate swears at the Cloth” was the headline. A reduced majority was the result!

He nearly got into trouble on another occasion as well. It was during the depression when things were not good. “What about the unemployed” shouted a heckler at one of the election meetings. “What can they afford to eat?” “Let them eat herrings” came the reply. At the time herrings were 2d a lb and all hell broke loose because of the insult!

Another early memory was looking from my nursery window into the Manor Farmyard. A splendid sight every morning. Fifteen heavy horses being prepared for work. Teams of three going off to plough or work the ground. Whatever was in season. Harry Pitcher was one of the Carters. Ken Westcott’s father was another.

I went away to a prep school called Heatherdown near Ascot in 1932. It was a four hour drive in a Singer Six. It went at sixty down hill and had a luggage rack on the back for the trunk. After Heatherdown came Eton in 1937. Pre-war Eton was a bit like Tom Brown’s School Days. I was not academic. Eton had wet bobs and dry bobs, those who rowed on the river and those who played cricket. The river was grand. I enjoyed it hugely. I finished by getting into the eight which rowed at Henley in a schools regatta in 1942 which we won. Being war time there was no official Henley regatta. Eton provided several of the boats. As no one had any petrol to take them by lorry, scratch crews rowed the boats up and came home by steam train. After the race we were all hyped up after having won. We set off on the 25 mile journey downstream to Eton. If you have ever rowed a boat you must be able to remember the feeling when it is going well. The whole thing depends on absolute timing. Clonk-swish-pause-clonk-swish-pause. After 25 miles the boat sped. It was a beautiful moonlit evening. We had our coach with us. He rode the whole way on a bumpy towpath on his bicycle. There were seven or eight locks for him to get his breath back We stopped for dinner at Skindles Hotel in Maidenhead. The final lap was two more locks and so home at about ten o’clock in the gloaming. I have never forgotten that evening and never will. The way to coach an eight is to take them on a twenty five mile row, but few people have the time today.

I joined the Navy on 10th Oct 1942, arriving at HMS Collingwood with my gas mask in its cardboard box. There were 5000 of us there and because of my background I was made what was called a Class Leader, in charge of a class or hut, about 30 of us. I had learnt a bit of jujitsu at Eton. That came in handy. There were four of us who were aspiring to become officers, who joined at the same time and took charge of adjoining huts and all went off to the same ship together. One of whom was Derek Mond. More of him later.

While at Collingwood the Bishop of Portsmouth was very kind. He and Mrs Anderson used to invite young sailors to their house for tea and baths. This happened several times. He later became Bishop of Salisbury and in 1962 he married us. It was a case where I thought he was my friend, but my new father-in-law had known him for a lifetime.

My father was still MP and a friend of the Captain. On one occasion he paid a visit to Collingwood and stayed with Captain O’Leary. At Divisions next morning he was there with the top brass on the dais for Church Parade. As Class Leader I had to stand in front of my Class. I could hear the mutterings behind me. “Who is that old …” and so on. In a way my father looked a bit like Molotov as he had been in London and was wearing a black Homburg hat. Later that morning we returned to our huts to write our Sunday letters home. I was called “Leader” by the rest of the hut. There would be a shout. “Leader. How do you spell Molotov?” One question was “How do you spell Popovsky?” At 11.30am we had Sunday dinner. Roast beef with Yorkshire pudding, plum duff and seconds. After that at 12.30pm Julian Mond and I were off to lunch at the Golden Lion in Fareham with my father, We had all there was to offer once again. They kept us on the run all day and we were hungry!

Julian Mond had also been at Eton with me. He was the son of the first Lord Melchet, the then owner of ICI and two years older. He was a brilliant brain and was researching into explosives for his father’s firm. He gave that up as he wanted to be in uniform and not in a reserved occupation. Sadly he was killed in a flying accident when going home on leave.

Then to my first ship. A hunt class destroyer, HMS Atherston. Immediately after joining we went to sea. A short trip but long enough to be seasick! It was from Harwich to Chatham for a boiler clean. That gave us three days in dock and a chance to nip up to London. The four of us set out by steam train. We had a night on the town and then required a bed. We were in uniform of course. Bell bottomed trousers and the little round hat. We required somewhere to stay the night. Derek said we were to stay at Claridges, close to where his parents lived in a big house in Grosvenor Square. By this time it was two in the morning. We swept through the main door of Claridges, Derek produced from his bell bottoms a crinkly white five pound note which he slipped into the hand of the night porter. We were given a suite on the top floor, but had to catch the 5.30am train to be back on board by 0700!

Then off to Gibraltar which took five days of seasickness! On to Oran, then finally to Bone where I had a respite from seasickness! We had been escorting a convoy to Alexander’s Eigth Army.

After a few months convoying supplies along the North African coast it was time for the four of us, who had all joined together, to go for officer training. Then to a ship in Scapa Flow. A Colony Class Cruiser called Jamaica. Fourteen months followed on Russian Convoys. I had the experience of being part of the last naval battle with Battleships when the Scharnhorst was sunk. A very interesting day.

Eventually the war ended and Jamaica took me to the Far East. There is no doubt that the most enjoyable year of my life thus far was 1945/46. I was having a very interesting time travelling the world and being paid (all be it not very much) to do it.

There are two incidents that come to mind. The good ship Jamaica arrived in the harbour at Trincomalee after a visit to Singapore. Trinco was a beautiful place, about the size of Poole Harbour but all if it deep water. My job when entering and leaving harbour was to be officer of the watch. This meant I relayed the orders from the captain down the voice pipe to the quartermaster. No telephone communication then.

I noticed a commotion at the far end of the harbour. Lots of small boats milling around. It appeared that a whale had got into the harbour and died. Tugs were trying to get a line around its tail to tow it out to sea. This was eventually done. When the tug was clear of shipping the crew slipped the tow. The whale gave a flick of its great tail and swam happily away.

News of the resurrection reached the fleet later. However the next day what should be seen in the harbour again but a very large whale. Panicky signals were flying round the fleet warning all small boats to keep clear. The whale was very much alive. A large area was made out of bounds.

After a time the problem resolved itself. The whale was seen to swim out to sea, but this time she was not alone, as she was able to take her calf with her.

Another incident that I enjoyed was my first command. It was an extraordinary vessel, about 150ft long, a large hold and heavy lifting derricks. A bridge that stretched the whole width of the ship with an enormous wheel in the middle. It had a very tall funnel and two steam engines that drove the thing at a maximum of three knots. My captain told me he had secured an interesting job for me. It was to take this barge back to the Andaman Islands where it had previously been used in the forestry department. The ship had been completely stripped. It had no stores. Everything was empty. Coal bunker empty, water tanks empty, not a rope to be seen. I have never seen so many and such large cockroaches.

My fellow officer was also an Old Etonian. Between us we tried to obtain the basics of life to make the vessel habitable. Long before we were ready, headquarters sent down 22 sailors and two petty officers. No food, no accommodation, only a difficult situation to sort out. Eventually we did and were given orders to go to the Andaman Islands 1,500 miles away. No way was the ship capable of doing that. Eventually after a series of tugs, one of which was a Royal Indian Navy Frigate, commanded by a four striped captain who was not amused by his ship being used for this purpose, we arrived at Port Blair. I obtained a signature for the ship and returned to India for two weeks leave. So I experienced two weeks of the British Raj.

After demobilisation I qualified as a land agent with a view to taking over at Symondsbury. Then went working on a farm in Denmark in 1950 and home to take over in 1951.

Another story about my father. He was badly wounded in the first war, and though he drove his car with gusto, he took longer than most to transfer his foot from the accelerator to the brake, his right leg having been badly damaged. Not so much traffic in those days thank goodness. Anyhow, when my sister Bridget married and moved to Kent, at a party and, talking to someone she had never seen before, she remarked that her maiden name was Colfox. The person she was talking to said “Oh. Are you any relation of that dangerous driver in Dorset?”

From 1951 to the present day is another story.’